BlackRock – Shadow Government?

Is It Too Big To Fail? Or Has It Now Got Too Big To Control?

There is a company out there that has more funds running through its systems than the entire GDP of the USA. A company that can and has used its clout to effect “societal change” whether we like it or not. A company with a direct connection with powerful politicians in the world has recently come front and center as it has started exploring investments in the crypto space and venturing into governance territory that will impact worldwide.

The BlackRock Behemoth

BlackRock is the world’s largest asset manager, and while many may have heard of it, you may be surprised just how much control it has over the financial markets. A control is afforded to it through leveraging our money, so there’s a strong chance that you and your money are connected with it somehow. It is a company that has its fingers in many pies, with over $10 trillion in assets under management.

They are also one of the most secretive companies in the world of finance. Trading and commodities are two areas of BlackRock’s business that have come under scrutiny from government regulators in recent years.

The Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC) has claimed that the process of trading commodities futures is not transparent and is likely being abused by large investment firms like BlackRock. One of the most controversial aspects of BlackRock’s business is the way they have been operating their so-called dark pools.

Blackrock’s political connections are extensive. Over the past couple of years, there has been growing concern about how much control large corporations like Blackrock exert over American politics and economic policymaking.

Although they claim to be a non-political organization whose only interest is maximizing shareholder value, it is clear that many large corporations like Blackrock do wield significant influence over how our government works and what kinds of policies it enacts into law.

Image Source: Financial Times

BlackRock’s Genesis And Growth Spurt

BlackRock is a New York City-based company founded in 1988 by Laurence [Larry] Fink and Ralph Schlosstein. Starting as a Bond Asset manager, it quickly grew into a financial services company that provides investment management, risk management, and fiduciary financial services to a wide variety of clients ranging from Central Banks to pension funds and individual investors.

In 1999, BlackRock became a publicly-traded company and continued its rapid expansion in the asset management sector. In 2006, the firm acquired Merrill Lynch's Asset Management business, which rapidly expanded its offerings in the equities sector. This was further compounded by the purchase of Barclay’s iShares in 2009. At $13.5 billion, this was one of the biggest deals in Asset Management history.

As a result, BlackRock quickly morphed from being a bond asset management company to an Index Fund provider. Index Funds, sometimes called Exchange Traded Funds, are collective investment vehicles that track the performance of a particular index or basket of Securities. They're hugely popular, not only because they're easy to invest in but also because they incur lower fees than more active investment management firms.

These benefits have also made index funds extremely attractive for more passive institutional investors, the most common being pension funds. Trillions of dollars are invested on our behalf and find their way into index funds of some sort. So there’s a strong possibility our money has been invested through BlackRock somehow. Either that or it's being invested by another index provider thanks to BlackRock’s technology.

The point is that BlackRock is a behemoth that invests on behalf of hundreds of millions of people, and what that means is it has an interest in nearly every company you can think of. Since BlackRock must invest funds to track indexes or other investing themes, it must invest in the underlying assets. If these funds track an equity index, BlackRock must take a stake in the underlying company, so BlackRock is often one of the largest shareholders of a company's outstanding shares.

These companies include some of the biggest Wall Street banks, like Goldman Sachs, JP Morgan, Bank of America, and Citibank. Essentially, BlackRock is one of the top three shareholders in the banks that keep the financial markets running.

BlackRock is also vested in the media with Comcast, Viacom, et al. Also, social media and tech companies with large stakes in Google, Apple, and Twitter. They even have stakes in the food industry with Mcdonald's, Chipotle, et al. Along with State Street and Vanguard, BlackRock forms a trio of the largest shareholders in the vast majority of publicly-traded companies in America.

Image Source: Corpnet

For example, according to a recently published paper by Corpnet, these prominent three asset managers are the largest shareholders for over 90% of all companies in the S&P 500. In fact, in the broader collection of all outstanding publicly traded companies, 40% of them have these three as their most significant shareholders. And it’s not just America; it holds considerable positions in companies in Europe as well.

A Slice Of The Real Estate Pie And Now Crypto

BlackRock has its eyes on cryptocurrency with BlackRock CEO, Larry Fink saying the firm is studying the crypto sector broadly, including assets, stablecoins, permissioned blockchains, and “tokenization,” where it perceives a benefit to its customers. We are increasingly seeing interest from our clients,

he said.

BlackRock is an investor in a $400 million fundraising round for Circle Internet Financial, the crypto-focused company that manages the stablecoin USD Coin. During a conference call in April 2022, Larry Fink said BlackRock has been working with Circle over the past year as a manager of some of Circle’s cash reserves. He said he expects BlackRock eventually to be the primary manager of those reserves. We look forward to expanding our relationship,

he said.

You might also be surprised to learn that asset managers like BlackRock have been competing with you regarding residential real estate. Last year, large institutional investors bought up entire property units to diversify their holdings. Just imagine, large asset managers could potentially be using your pension money to outbid you on a home. Despite how crazy all this sounds, it’s just the tip of the iceberg.

ALADDIN – BlackRock’s Genie Of Growth And Control

BlackRock has not only made a name for itself through its index funds, but it's also developed an institutional investing platform that is the backbone of the asset management system. The “central nervous system” is relied upon by nearly every billion-dollar capital allocator. It’s called Aladdin, an acronym for Asset, Liability, And Debt, Derivative Investment Network.

Since Aladdin’s humble beginnings as a time-saving system that BlackRock could use to report on bond positions automatically, it has grown over the years to become the operating system for the company that inhabits multiple data centers and is maintained by a group of between 1,500 and 2,000 people.

Aladdin is so integral to BlackRock’s internal risk management systems that around 13,000 BlackRock employees use it worldwide. Aladdin also became so sophisticated that BlackRock saw an opportunity to start making money from competing asset managers, institutional investors, and corporates by making the platform available to them. It would also allow these investors to manage their portfolios and model the inherent risk.

The list of companies that use Aladdin is vast, with over 240 external clients currently relying on the platform. Companies like Google, Apple, and Microsoft use it for their corporate treasury management. The $1.5 trillion Japanese government pension fund is also a client, as well as State Street and Vanguard.

So, in reality, BlackRock’s biggest competitors are effectively paying to use BlackRock's systems and, in the process, giving BlackRock access to reams of data about their portfolios. This data further helps BlackRock refine Aladdin and better model risk. Needless to say, because all these portfolios are linked, it certainly gives BlackRock the edge with Aladdin as a critical component in the global management of assets.

In 2020, an estimated $21.6 trillion sat on the platform, which is higher than the entire GDP of the United States at that time. Another comparison is if you were to empty the bank account of every one of the 7.6 billion people in the world, every single bill and coin, and place them all in a pile, it would be worth around $5 trillion.

So, this means that Aladdin has grown into a system that is responsible, directly or indirectly, for over four times the value of all the money in the world. Aladdin doesn’t make investment decisions, but its risk models inform the investment decisions of all who use it.

There have been many who have questioned whether this system poses a systemic risk to the market. For example, given how many managers rely on its analytics and modeling, does this create complacency and reliance that could give a false sense of security? What happens if there are inaccurate or erroneous readings? It's only a computer model, after all.

A UK regulator, the Financial Conduct Authority, reported that the failure of an extensive portfolio and risk system like Aladdin could cause serious consumer harm or even damage market integrity.

Jon Little, former head of BNY Mellon's international asset management business, told the Financial Times,

“The industry is becoming reliant on a small number of players such as Aladdin, yet regulators seem to be reluctant to regulate or intervene to supervise these key service providers directly.”

This video sums up the level of involvement BlackRock has with their technology, Aladdin has and looks somewhat like a terrifying science-fiction scenario, but it is happening today.

BlackRock’s Helping Hand

Did you know that BlackRock was instrumental in the bailouts and deals in 2008’s GFC? It was a key adviser to other big banks and the government itself. So BlackRock is not only a massive asset manager that controls one of the world’s most powerful computers, but it also offers advisory services.

It’s called the Financial Markets Advisory or FMA. It was born from the financial crisis as these big banks, along with the US Treasury and Federal Reserve Bank of New York, turned to Larry Fink of BlackRock for help and counsel on their predicament.

Through an array of government contracts, BlackRock effectively became the leading manager of Washington’s bailout of Wall Street. The firm oversaw the $130 billion of toxic assets that the U.S. government took on as part of the Bear Stearns sale and the rescue of A.I.G.

It also monitored Fannie Mae's and Freddie Mac's balance sheets, which amount to some $5 trillion. It provided daily risk evaluations to the New York Fed on the $1.2 trillion worth of mortgage-backed securities it had purchased to jump-start the country’s housing market.

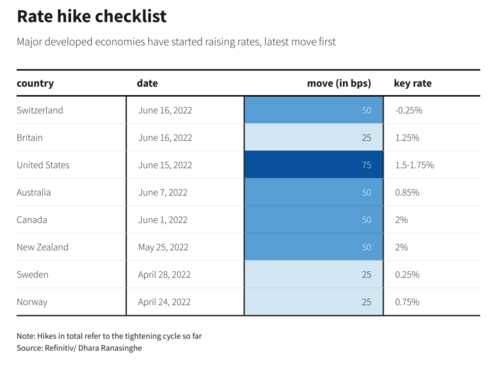

Eleven years after the financial crisis, we had another emergency, the pandemic, which brought on a level of spending that was many multiples larger. The FED embarked on an unprecedented bond-buying program and monetary stimulus. These were trillions upon trillions of dollars that are used to buy back not only treasury securities but, more risky, corporate bonds and mortgage-backed securities.

And, of course, they needed the advice of someone who knew about these types of securities. Thankfully, they had the industry experts such as Larry Fink on speed dial. It was later disclosed that BlackRock was central to the pandemic response. According to this New York Times article, Larry Fink was in constant contact with Jerome Powell and Stephen Minuchin in the days before and after the FED's stimulus program announcement.

According to a contract posted in March 2020, the FED hired BlackRock to help with the corporate bond purchase program. Although there was much more transparency about the terms of the deal compared to its work back in 2008, it meant that BlackRock was instrumental in that bond-buying program.

It again shows how reliant these officials have become on this behemoth of Wall Street. So it's clear that BlackRock has political influence or, at the very least, is aligned with some really powerful people. But perhaps more concerning about the firm is its power and intention to exert over corporate board rooms.

BlackRock’s Role And Goal Posts Have Shifted

As mentioned above, BlackRock and the top three asset managers generally are the largest shareholders in hundreds of Fortune 500 companies. What this means is that not only do they own the shares, but they also get board representation. These corporate boards are designed to help advise on company strategies, and board members can have much more say in a company’s strategic objectives.

Given that BlackRock invests on behalf of clients, it is considered a passive investor, meaning it's merely tasked with allocating capital and voting in the best interest of shareholders. Up until a few years ago, that's precisely what it did. However, in 2018, it all changed because, at this time, Larry Fink wrote a letter to the CEOs of some of America's largest public companies. This was the first salute in his pitch to better contribute to society,

“Society is demanding the companies, both public and private serve a social purpose. To prosper over time, every company must not only deliver financial performance but also show how it makes a positive contribution to society.”

This was a novel idea at the time but has since shaped the mood around investing based on ESG or Environmental Social and Governance principles. The primary modus operandi behind this investing methodology is that companies should not only be graded on their bottom line but also on how they impact society.

Image source: New York Times

This letter was a big deal. You had one of the most powerful investors on Wall Street saying that it would be using ESG criteria to grade companies, everything from their climate change records to diversity on their boards. Some wondered whether BlackRock really would carry out these plans for a more activist role; any doubts on the matter were laid to rest with some controversial shareholder votes.

For example, last year, BlackRock disclosed that as Exxon Mobil's second-largest shareholder, it was backing board changes proposed by an activist hedge fund. The fund in question was Engine No 1, and it's been trying to get Exxon Mobil to move faster in reducing its carbon footprint. The activist investor only held about $50 million in stock but had proposed some board members who Exxon claimed didn't possess the requisite skills to serve on the board.

As mentioned in this WSJ report, BlackRock also backed similar initiatives by voting against a board director of an Australian oil and natural gas producer called Woodside Petroleum. The reason for the vote was that the company was not outlining targets for emission reductions to its customers. So the world’s largest asset manager is showing it is more willing to use its heft to influence the policies of the companies it invests in.

Rich Field, a partner at the law firm King & Spalding, who focuses on corporate governance issues, said,

“BlackRock has strongly signaled that quiet diplomacy is not the only tool in its toolbox. We expect more votes for shareholder proposals and against directors in this and future years.”

Since 2020, BlackRock has stepped up pressure on more companies by publishing criticism with online bulletins about key votes. Some executives worry they could face lawsuits for publicizing details on labor or climate plans in areas where global disclosure standards don’t yet exist.

There are so many boards that BlackRock sits on that it could be hard to apply proper due diligence to these ESG votes. Some have complained BlackRock’s recent votes have come without warning or an adequate rationale. Ali Saribas, a partner at shareholder advisory firm SquareWell Partners, said,

“BlackRock’s approach will fuel a rising frustration among companies that believe BlackRock’s stewardship team will most likely apply a tick-the-box approach given the sheer volume of companies they passively own.”

Jessica Strine, CEO at advisory firm Sustainable Governance Partners, says,

“It would be very hard for a passive fund manager to support a shareholder proposal that addresses systemic risks but wades too far into dictating strategy.”

Investors propelled ESG funds to new heights in 2020, and federal agencies are watching.

WSJ explains why regulators have ethical and sustainable investment funds under review. Photo Illustration: Alex Kuzoian

Has BlackRock Gone Too Far?

Some may think this is good news for a better future. Still, one of the biggest problems with this approach is that it assumes that meeting these ESG criteria could be complementary to the shareholder returns objectives.

However, this is often not the case because meeting these criteria may come at the expense of potential company performance and long-term shareholder returns. For example, in the case of the Exxon proposal, unless these standards are applied to all competing companies in the field, you are hampering some to the advantage of others.

Many oil and gas companies are private or listed elsewhere, companies that don't have BlackRock as a shareholder and hence don't have to worry about meeting the same standards. They can compete as much as the law allows them to, and sometimes to the detriment of Exxon. This could lead to a fall in the value of Exxon shares and the company as a whole.

Now the same principles can, of course, be applied to the S and G angles of the ESG strategy too. Then, of course, you have the administrative burden and the unpredictable way this ESG mandate is managed.

The approach that BlackRock wants to take could hamper the efficient performance of a company's board and corporate strategy, which is unsuitable for that long-term shareholder value. Beyond the additional burdens that this could place on companies, you have the question of whether a company like BlackRock should have such a significant say in how society is shaped.

The Silenced Majority

Have all the stakeholders, the millions of us who have pension funds and invest in ETFs, been asked how we feel about these proposals? Are stakeholders polled on each one of these proposals? And how do we know there's no broader political agenda that could seep in should the winds of public opinion shift. Does this create a precedent for other large companies to follow suit? These are all relevant questions that need to be answered. It is, after all, good governance.

Many of us know BlackRock is a powerful company but to realize how far that power extends is an eye-opener, to say the least. As the world's largest asset manager, it manages an ocean of capital that gives it immense control over the financial system.

Given that it's the owner and operator of one of the largest and most crucial asset management platforms, many would argue that it's too big to fail, but more to the point, it's now too big to control. That's because BlackRock seems to be taking on a new mission beyond mere capital allocation.

The firm is looking to use its ESG mandate to shape the way that corporate America is run. It's also not as if politicians can really do much about it. Given BlackRock's connections with all of these higher-ups, it is more likely to call the shots than the other way around.

Of course, the mandate and goals of BlackRock may be benevolent and sincere, but you have to question how this power could be used in the future should it fall into the hands of someone who would use it for more than just ESG benchmarks? Money is power, after all, and given that BlackRock controls so much money, it has absolute power. And as the saying goes, absolute power corrupts, absolutely.

References:

The Wall St Journal

The New York Times

The Financial Times

CoinBureau

Also published @ BeforeIt’sNews.com: https://beforeitsnews.com/economics-and-politics

Tim Moseley

.jpg)

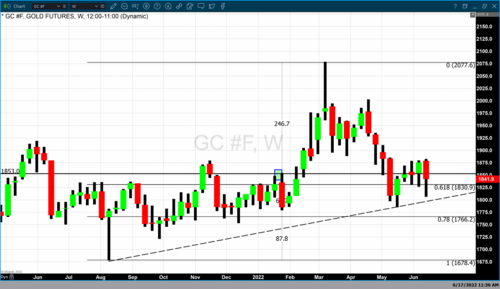

Gold hasn't lost its luster even as the Fed continues to raise rates – State Street's George Milling-Stanley

Gold hasn't lost its luster even as the Fed continues to raise rates – State Street's George Milling-Stanley.png) Image courtesy of

Image courtesy of  âââââ Image Courtesy of

âââââ Image Courtesy of

.gif)

.gif)